Battle of Shiloh

Today is the Anniversary of the THE BATTLE OF SHILOH

Today marks the anniversary of the first day of the Battle of Shiloh. April 6-7 1862. That battle began in the mists of a rising spring sun about 7am, 157 years ago this morning.The Union army of about 40,000 men had just disembarked over the preceding days from a flotilla of riverboats and ironclads at a river boat landing called Pittsburg Landing astride the low flat muddy Tennessee River.

The Tennessee River sweeps in a great big arch from its headwaters in western Appalachia through Knoxville and Chattanooga, bowing southward skirting through northern Alabama and Mississippi before turning northwest into the Father of Waters, the Mississippi River.

There was, and is today, a road to Corinth, Mississippi that runs nearby a little river port called Pittsburg Landing. If the Union Army, under Ulysses S. Grant, could steal a march south on that road before the Confederates could assemble a sizable resistance, the Union Army could conceivably cut the Confederacy in half. One of the vital east-west rail lines from Memphis and points west ran directly through Corinth to Chattanooga. There was another vital rail line, too, that ran north and south from Mobile, Alabama to St. Louis up North. Those rail lines crossed in Corinth. Where these four iron rails intersected, perhaps only a square yard of gravel-covered dirt, will become the most contested yard of earth in the history of American warfare. Over the course of the war, 100,000 men will be chewed up fighting over those rail lines.

It was a big, big gamble and we darn near lost. .

Confederate forces of about 40,000 men struck the Union army hard at a place called Shiloh. There was then, and now, almost nothing of note to give identity to the place. But there was in a little stretch of plantation land, a small church called Shiloh. And it was a horrible battle. It killed and maimed in 2 days more men than had been shot to pieces in all our wars up to that time. By the end of the evening of April 7th over 23,000 men were broken, dead or dying.

It was terrible.

I recognize that my fascination with thing gone by, event removed from memory, are considered eccentricities today, but I want to try to explain why this battle should be remembered.

First, because it was an appalling price to pay. No one anywhere, North or South expected these kinds of casualties. Bloodier battles will be fought later, but this was a wake-up call for our country. The war for union and eventually the destruction of slavery, was going to cost more blood and treasure than anyone could have imaged.

Was it worth this much blood for an abstraction called Union? Or was there something deeper that we had to find in ourselves and our idea of America as moral justification for sacrifices of horrifying magnitude?

Second, and I wish I could communicate this better, but, we the living, have responsibilities to the past. I know that sounds romantic and even quaint to those who have no God or any belief that men and ideas live beyond the grave—that things like justice and truth have substance only in our private physical existence. I am not one of these.

I believe we have a duty, even a promise to keep to those who fought to give us this place and abstract thing called America.

Those young men may have died for their mothers and fathers or to impress their girlfriends. They might have fought for Abraham Lincoln, but they also died, whether they knew it or not, for you and me. We the living. We have inherited a nation without slavery, a nation committed, no matter how inconstantly, to equality before law. And they fought for something I am personally very grateful for—a thing called freedom, no matter how imperfectly achieved. I owe them. It was not my blood. When others spill their blood for me—I owe them.

The words of the 13th 14th and 15th Amendment were written with the blood of thousands of young men who have left to us a legacy from the grave. And if you are a Christian, their souls are either present now in their reward, or will be resurrected on the latter day, and we will all be one nation again. One nation under God. Those faceless, nameless forgotten boys tortured in indescribable pain, crying for their mothers, their limbs torn from their bodies, their faces ripped open by exploding shells, whether you are secular or of my mind, they are still among us. They are still our boys. Our family. Not ghosts, but whispering spirits into our deaf ears that we too have a duty to the future. They are still with us here.

We owe them.

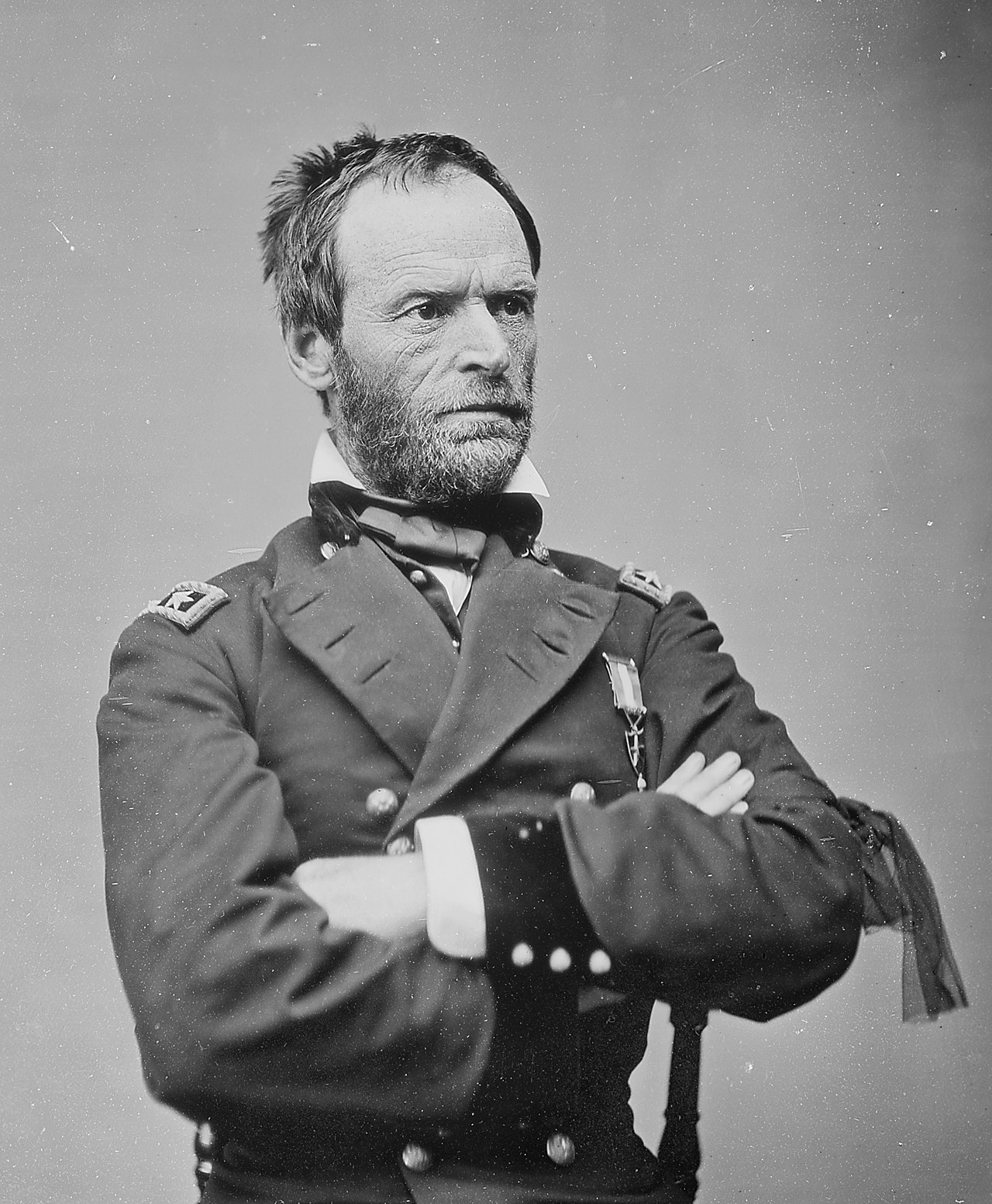

Third, this battle will produce one of the most enduring friendships in military history. Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. I can make a very powerful argument that the Civil War was won as much by their friendship as by the armories of Massachusetts. These two men will forge a trust that was as David of the Old Testament said of Jonathan, “a love surpassing the love of women”. They found brotherhood in the thick choking clouds of black powder smoke and gleaming Confederate bayonets of the Hornet’s Nest.

When those two young generals emerged exhausted and sweating from a battle they almost lost, there was a knowledge of an unspoken and unbreakable trust and solidarity. Each would do his duty to the death and for each other. Please don’t dismiss this as rhetoric or romance. I mean they would die for each other. Soldiers and men who have worked and fought together know this thing. And Sam Grant and Uncle Billy had it. And that made them an unbeatable team. They respected and loved each other, and by the way, they both felt the same about Lincoln who was a father figure to both of them.

Last, is an interesting collateral tale. During the choking hours when the Union line nearly broke, as tens of thousands of Confederate smashed against Grant’s and Sherman’s ad hoc defenses, Grant desperately required a young subordinate general name Lew Wallace to march his division with all dispatch directly to the battlefield. Unfortunately, the written orders that Wallace received were not clear and the young general arrived too late to relieve Grant’s exhausted men.

Grant never forgave Wallace.

That young man will be relieve of command and sent back to Washington DC to await orders. Eventually, after a number of minor positions, he will be given command of a small corps of 100-day volunteers in Baltimore—an unimportant backwater while the great civil war was raging over the entire South. It should have been a humiliating end to a young man’s career who had once had a very bright future. Wallace had been the youngest Major General in the United States Army. Now his career and reputation were ruined.

But then something remarkable happened.

In July of 1864 as the Confederate army strained desperately to hold Richmond, Robert E. Lee, sent Jubal Early in a great sweeping cavalry invasion of the North. His objective was to relieve pressure on the Confederate Army around Petersburg, VA and, if possible, capture Washington DC and burn it.

If General Early could burn Washington DC the international implications would justify military intervention by the Brits and French to assist the Confederacy. That would change everything.

Washington, DC, under no circumstance could be allowed not fall.

Now image you are Lew Wallace. You’ve been relieved of command for failure to do exactly what you were told. Wallace’s military responsibility was Baltimore and only Baltimore, not Washington. But being a good soldier and following his military instincts, he was perhaps the only person in the entire Union Army at that moment that seemed to know what was happening, and had the wherewithal to do something about. He understood what Lee was doing.

And he acted.

Lew Wallace marched his army west to the only place where his smaller force might realistically stop the enemy. He did not wait for orders or ask for confirmation of what he had to do. He knew what needed to be done, Without hesitation Wallace moved his small corps of about 5,000 men out of Baltimore to intercept Jubal Early’s vastly superior command.

And on July 9th 1864, there was a disparate struggle called the Battle of Monocacy. It was fought at the choke point of where the the B&O Railroad bridge fords the Monocacy RIver, about 50 miles west from Baltimore in a straight line toward Harper’s Ferry.

It only last a few hours, about six. And Wallace lost. Jubal Early pushed his 14,000 men through Wallace’s boys and over the creek. He possessed too many men and guns and cavalry. But Wallace held long enough. He bought time for Grant to ship reinforcements north by rail to defend DC.

And Washington was saved.

Wallace, of course, was criticized for not stopping the Confederate Corp. He had lost a battle.

And again he will be marginalized. But, over the intervening century and a half, cooler and more objective minds have concluded that Lew Wallace may very well have saved his country.

I can make an argument that the Battle of Monocacy is one of the most important battles in American history, not because it was a big battle or a victory, but rather because it shows how important one man is, when he does exactly what needs to be done, when exactly it needs to be done, without having to be told it needs to be done. That’s called a hero. Because had Monocacy not been fought, Washington DC might well have be captured and the Civil War might have ended much differently than it did.

One man at the right place at the right time, moved by nothing but his conscience.

I write this as an epiphany that comes now and then when I least expect it. Wallace must have been a man of remarkable character, because in marching out to meet his enemy he was not doing what he was told to do. He had been relieved of command for failing to follow orders. Grant wanted Wallace to follow his instructions to the T.

What would you have done?

Wallace followed his conscience. And he lost.

But now the part you don’t know.

You see, Lew Wallace, after the war, later in his life, would write the most popular book of 19th century America prose. It sold more copies than any novel other than possibly Uncle Tom’s Cabin. You see, Lew Wallace wrote Ben Hur, just recently made for a third time into a spectacular movie. It is the story of a man who lost, but won. It is a story about a man who followed his conscience.

I tell you this tale to remind you that these men still live with us—that we are brothers with those who came before. They live and move and speak to us if we have ears to hear. Their voices and their cries echo through the present age. They gave us a country. We owe them thanks. Today is the anniversary of Shiloh.

Remember.